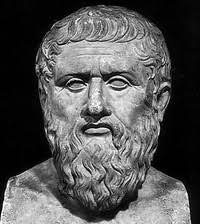

Plato

In Plato’s Republic we see one of the earliest attempts at a systematic theory of ethics. Plato wants to find a good definition for “justice,” a good criterion for calling something “just.” Maybe justice is “telling the truth and paying one’s debts.” But no, Plato says, for sometimes it is just to withhold the truth or not return what was borrowed.

How about “Do good to one’s friends and harm to one’s enemies”? But that doesn’t work, says Plato, because any definition of justice in terms of “doing good” doesn’t tell us much. It only repeats the question, “What is good (just)?” Plato’s suggestion for “justice” is twofold: justice for the state, and justice for the soul.

Justice for the state is achieved when all basic needs are met. Three classes of people are needed: artisans and workers to produce goods, soldiers to defend the state, and rulers to organize everything. But you cannot have a just state without just men, especially just rulers. And so we must also achieve justice of the soul.

Plato believed the soul had three parts: reason, appetite, and honor. The desires of these three parts conflicted with each other. For example, we might have a thirst (appetite) for water, but resist accepting it from an enemy for fear of poison (reason). Justice of the soul requires that each part does its proper function, and that their balance is correct.

Justice of the soul merges with justice of the state in that men fall into one of the three classes depending on how the three parts of their soul are balanced. One’s class depends on early training, but mostly, persons are born brick-layers, soldiers, and kings – depending on the balance between the three parts of their soul.

To bring about the ideal state, Plato says, “philosophers become kings… or those now called kings … genuinely and adequately philosophize.” Among other things, the philosopher king is one who can see The Good, that transcendent entity to which we compare something when we call it “good.” The idea of the philosopher-king still appeals to philosophers today, though it has rarely been achieved. It is against this ideal state, ruled by philosopher kings, that Plato can compare other forms of state. The state under martial law (Sparta) is the least disastrous. Oligarchy (Corinth) and democracy (Athens) are worse, and tyranny (Syracuse) is the worst. These problem states come from a lack of justice in the soul. For example, a state of martial law comes from the restriction of appetite by the wrong soul-part: honor instead of reason.